Guest Author – Mike Hynes

Palaeobiology MSc Graduate

Although I have spent large parts of my science career working on Mesozoic fossils, including my current MSc project on feathered dinosaurs, I want to take a moment here do discuss some lesser known applications of palaeontology. I have been lucky enough to have spent three years in Panama working for the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI), a branch of the Smithsonian that I think is doing incredible work. Whilst there, I worked with things from only a few decades to a few millennia old. Not the traditional idea of palaeontology, but it is still important to look into the recent past, especially to better understand what climate change has already done to the oceans. Here, I want to take a brief look at one of the many fantastic projects I was a part of.

Sponges are not often thought of as being important, beyond that they are the basal animal (ctenophores are not basal, don’t @ me). However, on coral reefs they are important foundation builders. Sponges filter the water column, and solidify loose substrate to give corals a proper environment to grow and become the beautiful reefs we see today. They also provide shelter and food for many other reef organisms. In fact, before corals, all reefs were sponge dominated, and with increased bleaching, diseases and acidification, sponges are again becoming the dominant builder of many Caribbean reefs. Therefore, tracking and understanding the change in the sponge community can help us to understanding how the reefs looked like in the past, how they have changed, and what further changes will we see? To test this, my collaborators took several cores from three reefs across the Bocas del Toro archipelago in Panama.

This video shows the difficulties of coring underwater as well as its importance: https://youtu.be/gMw8YcRdVnU

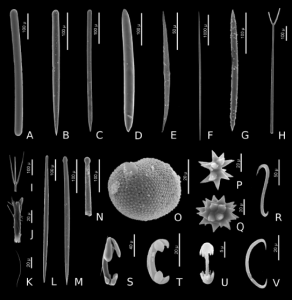

There I had the unenviable task of counting and identifying some 100,000 sponge spicules. Spicules are the microscopic mineralised component of the sponge you could classify as a skeleton. They provide stability and defence for a sponge. Here we looked only looked at the spicules composed of silica, as it is the most common type of spicule in sponges. If you have ever been to a beach, and felt like the sand was making your hands and feet itch as if you had handled fibreglass, that would be from these spicules.

After slaving over a microscope for literally a year, we have some results. This is where the project now gets interesting. Without getting too grossly invested in the data, what we found was an almost exponential increase of a specific spicule type over the last 400 years. This is important because this spicule type is known from only 3 out of 200 sponge species from Bocas. These 3 sponge species are large parts of the hawksbill turtles’ diet. Hawksbill eat mostly sponges, and specifically eat only a handful of species, as they are picky eaters. What we see then, is likely a shift in the sponge community towards a larger number of these hawksbills’ favourite sponges due to minimal numbers of turtles left in the area. Since before Columbus sailed to America to the modern day, hawksbill turtles in the Caribbean have gone from millions to only about 1-10% of that number. The loss of these predators has allowed for these sponges to become one of the dominant reef builders again. This would then demonstrate that humans have had a substantial impact on reefs even before fossil fuels and modern fishing practices. Hawksbills were used as both a source of meat and eggs for eating, as well as having a highly coveted shell to make tortoiseshell products by locals and European sailors alike.

However, I want to stress that we can’t think of the situation as hopeless. I firmly believe that even though humans have already made such large-scale impacts on the planet, we must remain diligent in our efforts to conserve nature. Coral restoration projects are yielding positive success (including the relatively new Coral Restoration Panama organisation) every day on helping reefs recover. I also hope that if you just take away one thing from this, it’s that palaeontologists aren’t always in a museum, or in a desert digging up bones. We can be found in every type of environment doing work to understand life in the past, and apply it to understand life now, and in the future.

Mike Hynes graduated from the University of Bristol in 2019 with an MSc degree in Palaeobiology. He is now a PhD student at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in the Netherlands.

Article edited by Rhys Charles

References

Lukowiak, M. et al. (2018) Historical change in a Caribbean reef sponge community and long-term loss of sponge predators. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 601: 127-137