Guest Author – Arthur Owens

Current Palaeobiology MSc Student

When thinking about ancient cats the first animals that jump to mind are often large and impressive species like the fierce Saber-tooths, Jaguars, and other big felids. Sadly, this is a view that is also mirrored in our research of historic cats, and a bias seen across all of science research. This article however is not about scientific bias but the third largest cat of south America, the Ocelot Leopardus pardalis, a species actually found alive today, brought forth by the recent discovery of a skull and part of a jawbone in Uruguay.

We all know Ocelots, whether from documentaries such as ‘Wildcat’, TV shows like ‘Archer’, or as my personal favourite Minecraft animal. These adorable yet fearsome predators are fascinating lenses into the palaeoecology of South America, and up until recently have had a very fragmentary fossil record. For those that aren’t familiar with these wild American cats,somewhat resemble larger, wirier housecats with leopard-like patterns, but should not be confused with our domestic overlords. Whilst Salvador Dali famously had a pet Ocelot, these wild animals should not be mistaken as pets. The spots of Ocelots are unique to the individual, and there has even been a single case of an albino Ocelot, which some sadly believe to be linked to deforestation.

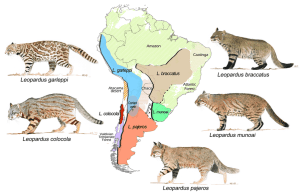

Their origins in South America date back to the early/middle Pleistocene (around 2.5 million years ago) when they migrated from the North alongside other Felids that are now extinct such as Smilodon. What the Ocelots got up to after migrating to South America is a subject of debate today, with a variety of perspectives that broadly split into two groups. The first group believe they gained traits characterising them as the Ocelots we know today there and diverging into different lineages as they adapted to environments and prey in South America. The opposing views believe in many different migrations to and from South America. This would highlight different traits being gained at odd points in their history and resulting in the diverse lineages we see today, as well as those such as the Machairodontinae (sabre-toothed cats) that went extinct. We observe this divergence from their ancestor species in traits such as the shape of their canines. Regardless of this spotty knowledge of their past, recent fossils and analogies with living Ocelots have allowed us to make a number of educated guesses about how and where they lived and thrived.

These tenacious felines today reside in tropical forests, dense scrublands, mangrove swamps and savannas, with their palaeoecology suggesting life in subtropical climates slightly drier than those of today, and with more defined winter seasons. They likely would have had similar diets as their surviving relatives, consisting of a range of small rodents, birds, lizards, and the occasional invertebrate. This can, in part, be inferred from features such as the shape of their forelimbs. This data provides us with a rough estimate of the forces they would be capable of exerting, and therefore the rough size range of their prey. This would then be taken in concordance with characteristics like tooth form and function.

Due to the importance of legs in day-to-day movements as well as hunting, we can also learn about how they could have navigated their environments. The adaptations their legs possessed such as bone proportions and claw shapes which could support climbing and leaping show a possible example of such adaptations. This gives us a piece of the puzzle by showing us what they are adapted to overcome when they were living in these past ecosystems. It therefore informs us of what their habitats, prey and even climates may have been like. All of this can be compared to what we know of the temperature and climate from geologists, as well as modern-day Ocelot ecology from biologists to help us narrow down as to what life would have been like in Uruguay from ice ages to the present day.

As a facsimile of living Ocelots, they were likely occasionally preyed upon by larger cats among other predatory species when given the chance, like many Jaguars do today. This opportunistic predation today is compounded by habitat loss as Ocelots are forced into more open areas by human activities like deforestation. Moreover, Ocelots were not free from competition from other intermediate mammals in their daily life, living alongside and possibly fighting with species such as the crab-eating fox, another mammal that managed to survive to the present day.

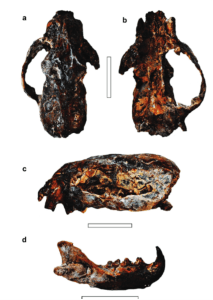

The fossils we have of Leopardus pardalis, the Ocelot, have generally just been the odd pieces of skulls and teeth. The recent breakthroughs in fossil Ocelot research came through from the discovery of more complete skulls, as for some reason many of the bones attributed to them in scientific papers lacked adequate, or any, justification for being members of Leopardus pardalis. The recently analysed remains have been confidently assigned to be from this lineage of Ocelots, and photos of these bones from Manzuetti et al (2023) are pictured below.

For the most part, these exciting discoveries by Manzuetti et al (2023) and Prevosti et al (2021) draw attention to some of our less studied ancient cats and demonstrate the resilience of these brilliant creatures who are facing arguably the most extreme adversity in their evolutionary history at the hands of deforestation and climate change today.

About the Author

Arthur Owens is a current Palaeobiology MSc student at the University of Bristol.

Article edited by Rhys Charles

References

Manzuetti, A. et al. (2023) The ocelot Leopardus pardalis (Linnaeus, 1758)(Carnivora, Felidae) in the late Pleistocene of Uruguay. Historical Biology. 35(1), 108-115.

Prevosti, F.J. et al. (2021) The fossil record of the ocelot Leopardus pardalis (Carnivora, Felidae): a new record from the southern range of its distribution and its paleoenvironmental context. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 41(1), p.e1922867

Julik, E. et al. (2012) Functional anatomy of the forelimb muscles of the ocelot (Leopardus pardalis). Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 19, 277-304.

https://www.biographic.com/no-country-for-old-ocelots/

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341726517_Taxonomic_revision_of_the_pampas_cat_Leopardus_colocola_complex_Carnivora_Felidae_an_integrative_approach