Guest Author: Sophie Pollard

Palaeobiology MSc Student

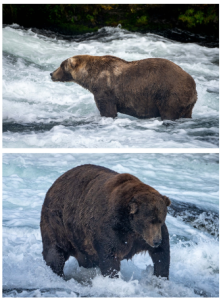

While citizens of the city of Bristol and the rest of the UK will remember the summer of 2022 for its record-breaking heatwave, records of a different kind have been set in the Bristol Bay area of Alaska, with sockeye salmon returning in higher numbers than any recorded before. This is great news for the fauna of Katmai National Park, and by extension, for fans of Katmai National Park’s Fat Bear Week, an annual event in which the bears of Katmai compete to see who best drags the competition, by how much their bellies drag along the ground.

Each year, between the months of June and October, the bears of Katmai national park and the Bristol Bay area (Alaska) race against the clock to put on the pounds before they hibernate in winter, a way of life I’m sure many of us aspire to. And for an area which boasts more brown bears than people, and the healthiest run of Sockeye salmon on the planet, it’s a great time to celebrate the richness of the Katmai and Bristol Bay ecosystem with some chubby Ursidae. Fat bear week began in 2012 and is now celebrating its 10-year anniversary of live explore.org cameras posted at Brooks Falls, and of course the public vote to determine which famous bear has put on the most blubber.

This presents a great opportunity to dive into the geological and ecological history of Katmai national park and the wider Bristol Bay area and into the fascinating evolutionary history of the brown bear.

Geological Significance – Volcanic Activity

Katmai isn’t only famous for the enormity of its bear population (in both number and size). In fact, the area owes its national park status to its unique and fascinating geology, particularly for its volcanic activity. The park has over a dozen active volcanoes, and eruptions are common within its boundaries, the largest and most famous being the 1912 eruption of Mount Katmai and Novarupta volcano, the largest volcanic event of its century.

Huge amounts of ash and pumice were ejected from the Novarupta crater, destroying almost everything that stood in its way. Volcanic deposits as thick as 300 feet would cover over 40 square miles within a matter of minutes. Meanwhile, the top of Mount Katmai collapsed in on itself, forming a caldera.

Geological surveying performed by the National Geographic Society over the next few years would reveal the volcano and the surrounding areas to be much changed. The adjacent Ukak river valley, once covered with shrubland and tundra, was now completely covered with pumice and ash, which formed a multitude of steam and gas producing vents (fumaroles) as it cooled. The area is now known as the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, and it was largely because of the efforts of those that discovered the feature that Katmai was designated a national monument in 1918.

Another famous feature of the park is the glacier that sits on the inside wall of the caldera formed by the collapse of Mount Katmai in 1912. This means that the glacier is possibly the only one in the world to have a known date of origin.

A Short History Of Brown Bears

The word “bear” comes from the old English “bera”, which in turn, came from the Proto-Germanic “bero” or brown one, which is thought to have been invented as a euphemism for the terrifying apex predators of ancient Northern Europe, a prehistoric “he who must not be named”. Other northern European language groups went a slightly different route with their re-naming of the iron age Voldemort, with Slavic languages adopting words meaning “honey-eater”, and Baltic groups going with words meaning “hairy” or “shaggy”.

The predecessor of the modern-day brown bear is generally believed to be the Etruscan bear, or Ursus etruscus, which lived from around 5.3 million to 10, 000 years ago, when it was wiped out during the most recent glacial period. It would have been similar in size and build to the modern-day black bear and came to be found all across Eurasia, and some parts of North Africa.

The oldest known brown bear fossil was found in China and is estimated to be roughly 0.5 million years old, but it is thought that the brown bear would have first evolved around 800,000 years ago before spreading throughout the Asian continent, reaching as far as Japan by 340, 000 years ago.

Entering Europe not long after, roughly 0.25 million years ago, the brown bear would likely have come into contact with its sister taxon the cave bear, which has also descended from the Etruscan bear a few tens of thousands of years before.

Cave bear remains are very common all across Europe. One cave in Austria (part of the Drachenhohle caves) was even found to have the bones of over 30,000 individuals, which would have accumulated over many centuries. With teeth adapted for eating vegetation, the cave bear would have been at least mostly herbivorous but would have spent its summers putting on fat before hibernating for the winter months when food was scarce, much like the modern-day brown bear.

The species coexisted with brown bears in Europe for several thousands of years before they finally went extinct around 10,000 years ago, and the exact reason for their disappearance is somewhat of a mystery. Competition for space with the brown bear would likely have played a part, but cave paintings portraying the hunting of cave bears by humans point fingers at another culprit.

The movement of brown bears into the Americas is a little more complicated. It is thought that the first brown bears in North America would have crossed the Bering land bridge (which would have stretched between Russia and Alaska during periods of low sea level), before 100,000 years ago, however, it is now widely believed that it took multiple waves of migrations for the brown bear to colonise the North American continent.

The first brown bears to appear in North America were more or less wiped out prior to the most recent ice age event, possibly due to a period of warming temperatures, which would have caused a change in the abundance of various plants, and therefore in prey animals. It wouldn’t be until the next glacial period when sea levels sank and the Bering land bridge was once again exposed, that the brown bear would recolonise the continent, Likely alongside the first humans to settle in North America.

Brown bears are present all across the northern hemisphere today and are intelligent enough to figure out a way to thrive even in our own increasingly urbanised environments, with one Yosemite forest ranger going as far as to state “there is considerable overlap between the intelligence of the smartest of bears and the dumbest tourists” when questioned about the design of bear-proof bins.

The history of the brown bear is one that demonstrates how vulnerable to change our ecosystems can be, but also the immense potential for species to adapt to a changing world. what better reason to celebrate the ecosystems that still thrive across our planet, and to protect them for future generations to enjoy?

References

Explore.org live bear cam (Brooks Falls)

Sophie Pollard is a current Masters student of the Palaeobiology course at the University of Bristol.

Edited by Rhys Charles