Guest Author: Dr Romain Sabroux

Marie Curie Fellow in Earth Sciences, University of Bristol

I have to make a confession. I am not much of a diver.

As a marine biologist, this probably sounds odd. But if you make something as demanding as SCUBA diving, especially when you are on an actual scientific expedition and that you need to sample several times per day for a whole month, you need a good reason. My reason would be the animals I have been studying for eight years now: the pycnogonids, also known as sea spiders.

Sea spiders are arthropods – those animals with an exoskeleton and articulated legs, like spiders, insects, crabs and millipedes. Pycnogonids have four pair of legs but they are not spiders. They live in the sea, but they are not crustaceans. They are a group apart, characterised by a long proboscis at the tip of which stands the mouth; by a tubercle on the top of their head, which carries two pairs of eyes looking in all directions like a periscope; by an often very tiny and slender body; and by their long legs, in which the digestive and reproductive organs spread. They even use their legs to lay their eggs! Sea spiders live on the bottom of the seas all around the world, looking for the sponges, anemones, corals, algae, detritus, and all the other things they may feed on.

In our regions, sea spiders are really, really, inconspicuous and small. It is almost impossible to see them when you are diving. That does not mean you cannot collect them: in the field, divers sample bulks of algae, sand, muds, etc. that I can frisk back in the lab under a microscope. In the end, I see far more sea spiders staying all the day in a lab, than any diver on the field.

Note that not all sea spiders are small however, as some gigantic species (with a leg span of several tens of centimetres) dwell in the Antarctic Ocean or in abyssal waters. But I am very sensitive to cold… not mentioning to 600 bars of water pressure.

Jurassic Sea Spiders: The Same, But Bigger!

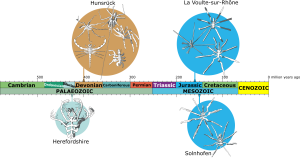

We know very little about the past diversity of sea spiders; only eleven fossil species have been discovered that are unambiguously identified as pycnogonids, and their fossil record is gaped with long hiatus of hundreds of millions of years. Sea spider fossils are only found in fossiliferous sites of exceptional preservation, with peculiar conditions that foster even the preservation of the most delicate animals.

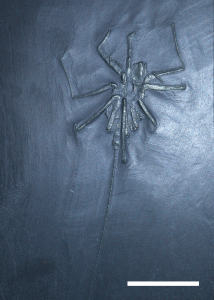

Two of these sites were found respectively in southern France and southern Germany, in the sites of La Voulte-sur-Rhône and Solnhofen. They provided us with precious testimonies of the sea spiders living in Europe some 150 million years ago, during a period called the Jurassic. While they clearly belong to sea spider species or families that do not exist nowadays, their body plan was very alike the extant ones. Remarkably, these species were also quite big (up to 12 cm of leg span). A dive to catch would have probably been lovely. But the biggest species found in the Jurassic were likely living in a level of the sea called the “aphotic” zone, that is the sea depth at which the light from the sun fades. We know this from the morphological adaptations found in the species which lived alongside them, including large eyes. It is also coherent with the families of some of the sea spiders found in these fossil sites. So much for a dive in the Jurassic.

Swimming With The Devonian Sea Spiders

But I know of an even greater spot for SCUBA diving. In Western Germany, some 400 million years ago. The biota of Hunsrück is a remarkably well-preserved witness of a shallow waters environment of a period called Devonian. Sea lilies, starfishes and brittle stars were covering the bottom of the sea, which was also navigated by diverse armoured fishes, trilobites, eurypterids, and even marine scorpions (Palaeoscorpius). There were also sea spiders. And what sea spiders!

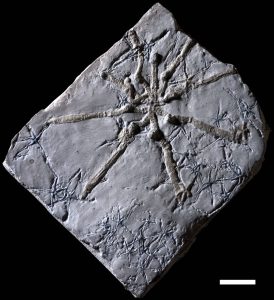

These were remarkably different from the species we can observe today. The structure of the legs does not correspond to extant species, and is relatively variable between species, suggesting they belong to very divergent groups. The base of the legs presented strange annular structures, the nature of which is not yet well understood. They also presented a long posterior abdomen made of several segments, which totally differ from the extant species that have only a small unsegmented bud at the same position. One of the fossil species, Flagellopantopus blocki, had a very long flagellum. Another one, Palaeopantopus maucheri, seemed to have no head at all.

Though my favourite sea spider fossil ever was also the most abundantly found: Palaeoisopus problematicus. The curious name of this species comes from the difficulties that palaeontologists experienced to identify it. It was initially thought to be an isopod, a group of crustacean that includes, among many others, the terrestrial woodlice (most isopods are actually marine). This mistake was rapidly “corrected” later on, but palaeontologists kept mistaking the abdomen for the head for over 30 years! This remarkably large species had a relatively broad body compared to extant species, and its abdomen was particularly long and divided in five segments. But the most remarkable feature of Palaeoisopus, were their four pairs of large, flatten legs. Their paddle-shape articles are likely to have been used to swim; its first pair of legs also present long, curved claws, and it is likely they used it to catch their preys. Now I know that my opinion may be quite unpopular here, but I would have loved to swim with gigantic swimming sea spiders. Sadly, I can’t.

The Blues Of A Palaeontologist

It is likely that sea spiders like Palaeoisopus, Flagellopantopus or Palaeopantopus belong to different groups of sea spiders than the extant ones: they shared many morphological features and a long common evolutionary history, but at some point their phylogenetic tree split into a few groups. As it seems, most of the lineages of pycnogonids disappeared at some point between the Devonian and the Jurassic, leaving only one remaining group: the pantopods. This is the unique surviving lineage that latter diversified in the Jurassic species, as in the modern ones.

So why were all other lineages suddenly wiped out? And when? These are some of the questions I try to answer in my research.

The evolution of pycnogonids echoes with an idea that shocked me a lot when I read it for the first time as an undergraduate student. An idea proposed by Stephen J. Gould in his book Wonderful life, a passionate reflection over the diversity of Burgess Shale (a fossil fauna of marine invertebrates living 125 million years before Palaeoisopus). According to Gould, evolution proceeds by decimation of lineages, followed by propagation within the boundaries of the surviving groups; rather than in a progressive, continuous diversification and complexification of life. Something quite like this may have happened with sea spiders. Their past diversity was rich in forms, body plans, and probably in their biology and their ecology. But most of this diversity disappeared somehow, and only pantopods diversified afterward, always relying on the same fundamental body plan. It is likely that we will never see something as beautiful as a swimming sea spiders again.

I sometimes get melancholic thinking about all these beautiful things that have existed, and that I will never see. But there is some comfort in thinking that some groups, including pantopods, have withstood the test of time and diversified in a wealth of colours, morphologies, biologies, and habitats, eventually here for me to gaze upon, through the lenses of a microscope.

Dr Romain Sabroux is a Marie Curie Research Fellow currently working in the Palaeobiology Department at the University of Bristol.

Article edited by Rhys Charles

References

Sabroux, R. et al. (2019) 150-million-year-old sea spiders (Pycnogonida: Pantopoda) of Solnhofen. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 17: 1927 – 1938