Guest Author – Jack Lovegrove

Palaeontology & Evolution MSci Graduate

Ichthyosaurs are one of those groups of prehistoric animals that always seem to play second fiddle to dinosaurs in popular science (with the notable exception of the BBC series ‘Walking with Dinosaurs’). They are usually only mentioned as a way of demonstrating convergent evolution with fish rather than as fascinating and varied animals on their own right. To add insult to injury they are often mistaken for dolphins by well-meaning museum patrons. So, it’s time to set the record straight; let’s dive into the staggering diversity of these “Fish lizards”, and what better place to start than the fantastically named Excalibosaurus.

As if that wonderful name (yes, it is named after the Arthurian sword) wasn’t enough reason to talk about it Excalibosaurus is also a pretty weird and interesting animal. From the neck back it has the long, streamlined body, fins and crescent tail fin typical of the advanced group of ichthyosaurs known as pavipelvia. But it is from the neck forward that things get weird. Excalibosaurus’ rostra, the scientific term for its snout, is extremely long and thin, and its lower jaw is only three quarters the length of the upper. This means Excalibosaurus possessed a huge overbite, with its tooth studded upper jaw extending sword-like (hence the name) away from its stunted lower jaw. This rather extreme feature would certainly have made it stand out as it swam through the seaways of Jurassic Somerset 190 million years ago.

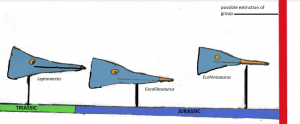

One of the most important areas of study within palaeontology is of how extinct and living organisms evolved, and Excalibosaurus tells us some exciting things about how it and its relatives evolved. The family of Ichthyosaurs that it belongs to is known as Leptonectidae and contains three other described genera, Leptonectes (which lived across the Triassic-Jurassic boundary 200-190 mya), Eurhinosaurus (early Jurassic 180-170 mya) and Wahlisaurus (which lived around 199 mya ago in the earliest Jurassic). If we place the heads of these animals in chronological order from Leptonectes to Eurhinosaurus, we can see how the groups specialised features became more and more pronounced over time.

In Leptonectes a slight overbite is visible; having a big overbite clearly gave some kind of survival benefit to those individuals that possessed it as, by the time Excalibosaurus evolved, its lower jaw development had been stunted to the point it was a full quarter shorter than the upper jaw. This trend towards this reduction reached its peak in Eurhinosaurus, the youngest member of the group, where the lower jaw was only half as long as the upper. And then our fossil record of these extraordinary animals stops. It’s possible that the extremely specialised lifestyle suggested by their skulls made them more vulnerable to extinction.

But what was said lifestyle? The short answer is that scientists aren’t sure, mainly because fossils of Excalibosaurus are so rare! While pulling a new specimen out of the stone won’t quite make you the King of England it will make you very popular among certain palaeontologists as only 2 fossils are known to science. Luckily for us one of these fossils (the original holotype) is displayed in the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery where you can go and guess at the function of its weird rostra.

Maybe it used it to slash through shoals of fish like the modern swordfish (which interestingly enough also develops its “sword” by slowing the development of its lower jaw)? Or alternatively did it use it to dig around for small animals in sand on the seafloor? It’s one of those exciting questions in palaeontology that is just waiting for the scientists and fossil hunters of the future to answer!

Jack Lovegrove graduated from the University of Bristol in 2021 with an MSci degree in Palaeontology and Evolution. He wrote this post whilst a Second Year undergraduate at the university. Jack is currently studying for a PhD at University College London.

Article edited by Rhys Charles

References

McGowan, C. (1986) A putative ancestor for the swordfish-like ichthyosaur Eurhinosaurus. Nature. 322: 454.

McGowan, C. (1988) Differential development of the rostrum and mandible of the swordfish (Xiphias gladius) during ontogeny and its possible functional significance. Canadian Journal of Zoology. 66: 496-503.

McGowan, C. (1989) Computed tomography reveals further details of Excalibosaurus, a putative ancestor for the swordfish-like ichthyosaur Eurhinosaurus. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 9: 269-281

McGowan, C. (2003) A new specimen of Excalibosaurus from the English Lower Jurassic. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23: 950-956