As this article is being first posted, the world lies on the precipice of the next big palaeo-media drama debacle. One week from today, the movie “65” will be released in cinemas, an action film that, judging from all trailers and pre-release information, can be best summed up as ‘Adam Driver from the future shoots dinosaurs.’

What happens next is inevitable. The palaeo world will erupt into fiery discourse online, with countless posts, videos, and articles discussing the designs and scientific accuracy of the dinosaurs depicted in the film. Some will violently cry foul, others will say that’s just a movie and to not make such a big deal over it. But I’m not here to talk about the dinosaurs themselves at all, I’m interested in the title of the film, which is sure to be another big talking point.

The movie is called “65”, with the idea being that due to some time-travel shenanigans, the characters find themselves 65 million years in the past. Any casual dino fan will be very familiar with that date as being the time when the dinosaurs supposedly went extinct. The only problem with this, for the sake of them and the film, is that it isn’t really.

By the best estimation of current science, the dinosaurs went extinct closer to 66 million years ago (mya). Only one number different, it seems a relatively small margin of error, until you realise that this leaves the new film with a rather glaring plot hole of being a dinosaur feature set over half a million years after the extinction of the dinosaurs. If you went to see a regency period piece and the drama all took place in the Mammoth Steppes of the mid-Pleistocene, you’d have some questions.

So how is it that we know the time the dinosaurs became extinct, and why do so many of us have it just that little bit wrong?

The study of the earth’s timeline is known as geochronology, with the dates often generated by a process known as radiometric dating. This involves looking at radioactive isotopes within the rock. These isotopes decay to their stable forms at a predictable rate (notably looking at their half-life – the amount of time it takes for the amount of the radioactive isotopes to half). A common example is the isotope Uranium-238, which decays into the stable Lead-206. By looking at the ratio of radioactive to stable isotopes, the date of the rock can be calculated.

As that fairly dry and still quite technical description highlights, it’s a rather laborious area of science. Hence why it never made it into the mainstream of popular science in the same way as other parts of geology, like volcanoes. ‘Mountain go bang’ is just easier to grasp. But nevertheless, results from these studies have been used to give numerical date values to the groups we had previously defined almost purely from their fossil assemblages and rock differences, the eons, eras, periods, and stages.

These boundaries are usually marked by some substantial change in the climate, periods of volcanism, or the presence and absence of certain indicative animal and plant species. As far as these boundaries go, there aren’t many more marked than that which spells the end of the Cretaceous.

We’re all familiar with the story of the asteroid impact which spelt the end of the dinosaur age. This impact left a mark in the rock of the earth beyond just the huge crater on the Yucatan Peninsula. It also resulted in a layer of rock rich in the element iridium which can be found all over the planet. Few periods have such an easily defined mark of their end than the solid line in the rock which calls the Cretaceous to a close. It is this line which is defines the date of the dino extinction.

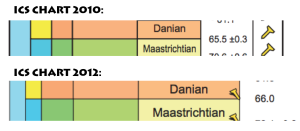

Every few years, with more precise equipment and a refined process, the dates are re-tested and a new official geological timescale announced. This often results in some dates changing by small decimals, fluxing over a few thousand years or so, usually bothering none but the most pedantic daters. But in August 2012 a timescale was published by the International Commission on Stratigraphy with one very substantial update; that familiar time for the dinosaur extinction had shifted from the old faithful 65, to 66 million years ago.

Nothing had really changed; the Cretaceous hadn’t magically become further away in time. It was simply a matter of a more accurate recording being made, and us updating our labelling of the boundary accordingly.

Over ten years have now passed since this update, but the news clearly hasn’t really trickled through to the mainstream yet. So why is that?

A large part of the reason could be that first impressions are key in palaeontology (and science media in general); it’s the initial discovery that makes the banner headline news, and the refinement to accuracy is reported quietly, buried deep in the niche media outlets, if indeed it’s lucky enough to get a press release at all. When the science first gave a proposed date for the extinction of the dinosaurs they said 65mya, and that’s the version of events that stuck.

Only having been updated in 2012, this means that when the vast majority of adults in the population were growing through their dinosaur-phase as children (everyone has one) it was that 65mya figure they kept hearing. Depending on the documentary, book, or game they were experiencing, the looks of the dinosaurs might have changed, some of the quoted science may have differed, but there was one fact that was always mentioned, and was the same every time; ‘The dinosaurs went extinct 65 million years ago.’ It ensured that it was one fact that really stayed with you.

It even made it well beyond just educational media and into the mainstream thanks to that old friend/bane of palaeontology, ‘Jurassic Park’. When the movie first launched thirty years ago, it memorably did so with the tagline ‘An adventure 65 million years in the making’ printed on every poster and announced at the end of every trailer. Considering the impact and scale of this film’s popularity, that number and dinosaurs became ever more intertwined.

In fact, that number actually became so synonymous with dinosaurs that it became the go-to answer for time no matter the context. Forget the extinction, whenever you ask someone “When did the dinosaurs live?”, 65 mya is still usually the most popular answer. It points to another fairly regular misconception about the dinosaurs, which is that people don’t often realise just how long they as a group were on this planet.

Sure the dinosaurs went extinct at 66 mya but they first appeared closer to 230 mya, meaning the dinosaurs were around for about 170 million years. Considering that our genus, Homo, has only been knocking about for around 2.5 million years, we’re really in no place to undermine the achievements of our dinosaurian friends. When asked the question of when the dinosaurs lived, you could give a truly huge range of answers. But nobody ever seems to say the safe, accurate, and pleasingly rounded figure of perhaps 100 mya, they regularly say 65 mya. As if the first dinosaurs born may have seen the asteroid coming if they lived to be grandparents.

But perhaps it’s too cruel to dismiss those who say 65 mya as a time you can find living dinosaurs, as it does at least have a logic behind it. Other pop-culture features have been far more removed from the mark. The song “Everybody walk the dinosaur” clocks them in at 40 million years ago, “The Flintstones” has them only 12 thousand years ago, and the film “One Million Years BC” placed them… well take a guess. And of course that’s before we get into the myriad of productions which have them still alive on some hidden volcanic island (a la “The Lost World” and “King Kong”) or somehow surviving in the core of the planet (“Land of the Lost”, “Iron Sky 2” and, bizarrely “King Kong” again).

So “65” may be far from the first palaeo pop-culture venture to be wrong about the date of dinosaur life, but it is perhaps the most frustrating of them all. Because frankly there isn’t really any excuse for it. Hollywood films have budgets of multi-millions of dollars and take years to make, and with all that money and time they apparently didn’t even ask a single person who could have told them that the very premise of the film was incorrect. It would have taken one second, and then they wouldn’t have spent a fortune marketing a film that somehow manages to contain a fallacy within its literally two-character-long title. It’s no wonder this film will surely cause a lot of palaeo discourse.

Though perhaps the best course of action is to avoid the discourse entirely. And that is why, when my fellow palaeontologists are all out hate watching ‘65’, me and my fellow sophisticated purveyors of fine arts shall instead be indulging in our seventh screening of ‘Cocaine Bear’, good day sir.

Rhys Charles is the Engagement Officer for the Earth Sciences department of the University of Bristol, and has headed the Bristol Dinosaur Project since 2016. (@tweetodontosaur)

Article edited by Anna Lim

References

65 (2023) dir. Scott Beck & Bryan Woods. Sony Pictures.

International Chronostratigraphic Chart (2012) International Commission on Stratigraphy