I’ve previously talked about one aspect of my Masters project on this blog, discussing the poor benthic crustaceans of Jurassic Somerset. If somehow you missed that blockbuster entry you can find it here. Sorry if the ending has been spoiled for you because of all the conversations and memes it no doubt inspired over the past few months. But there was more to my project than what was scurrying across the sea floor, I also looked at the monsters floating above them. To understand them, you first must ask one question; what on earth are Thylacocephalans?

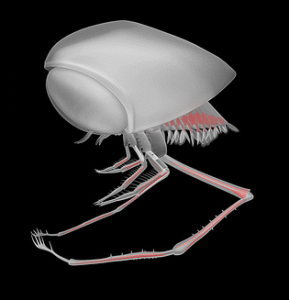

At first glance a thylacocephalan looks like an invention of science-fiction. Let’s start with the body, which is the most regular looking part of the animal, and yet can still best be described as an inverted taco. Thylacocephalans are arthropods, and this is their carapace, a tough exoskeleton, thus making them hard-shelled tacos, inferior food but superior defence.

The eyes of the animal protrude from a notch in the front of the shell, and this is where things truly get weird. There were some species with perfectly respectable arthropod eyes; little stalks appearing like a cross between a snail and a beetle. Somewhat odd perhaps, but nothing spectacular. And then you get the likes of Convexicaris and relatives, who have dedicated the entire front half of their bodies to make way for a singular giant eye, or perhaps two giant eyes for that binocular horror.

Similar to many arthropods, most famously the insects, thylacocephalans have compound eyes. Many individual receptors, called ommatidia, work together to form a complete picture of the world around them. With eyes so massive it’s fair to say that these arthropods certainly relied on their vision to find prey and avoid predation.

They say when you go to the gym you should focus on workouts that will exercise your whole body and not focus too much on one area. Otherwise you may end up a little oddly proportioned. This advice was skipped by Thylacocephalans. When not being distracted by the nightmare of Thylacocephalan eyes you may let your own take in the rest of the body and pick up on the other distinctive feature these beings possess, namely enormous rear appendages hanging ominously below the body. The first few pairs of legs look proportional to the size of the body, but the final pair are comically oversized.

The functionality of these limbs is relatively straightforward. They are tipped with hardened spikes or chelae; claws which can be used to precisely hold and cut up objects. They are so long so they can curl under the entire length of the body and rise up to meet the mouth at the front. Clearly these were used for holding prey items and bringing them up allowing the animal to feed whilst moving through the water.

So ancient monsters with all seeing eyes, enormous and hench claw-ended limbs travelling through the seas devouring prey; surely the marine reptiles were lucky to hold their position as the most feared top predators of the Mesozoic seas. Well, they would probably have been quaking in their flippers a little more if Thylacocephalans were not quite so small. The largest thylacocephalans ever recorded (the genus Ostenocaris of the early Jurassic) topped off at around 2.7cm in total body length. That’s around the same size as your average ichthyosaur tooth.

Being so small thylacocephalans lived a mostly pelagic lifestyle; that is to say they were free floating in the water column. Small pairs of appendages at the very rear of the shell could beat in unison and allow the animal to actively swim around like a shrimp, but if a strong current decided to come along and wash these little arthropods away there was realistically very little they could do about it.

A question remains of how exactly the thylacocephalans were affiliated in the great family tree of joint-legged exoskeletal ancient beasties. This a somewhat debated topic as the group shares features that could link them to the crustaceans (namely the anatomy of the mouth and gills, and the structure of the carapace), but whether they are true crustaceans in the same way as a classic lobster or ostracod is currently still uncertain.

We do know that, whatever they were, thylacocephalans were here for a long time. Fossils of this group can be found back to the Silurian. However some controversial fossils suggest a Cambrian origin, first appearing alongside some of the earliest arthropods. Their class expiration date is a lot more certain though. After putting in a good innings, they finally went extinct at the end of the Cretaceous 66 million years ago. This puts us now a little over halfway in the official period of mourning the thylacocephalans deserve.

By now you are surely all asking how this relates to the research that I conducted as a Masters student in 2015; what makes the thylacocephalans of the Strawberry Bank so interesting?

Well, firstly their very existence here is notable. The Strawberry Bank specimens represent the very first confirmed occurrence of the class Thylacocephala in the United Kingdom. This is hardly surprising given their abundance in mainland Europe, but it is still nonetheless worthy of note. It may not have caused the same splash in the scientific world as the discovery of say, dinosaurs, but it has only been five years since this discovery was made. Almost thirty years passed between the discovery of Megalosaurus and the unveiling of the Crystal Palace Dinosaur sculptures, so if any giant sculptures of Thylacocephalans happen to be raised there within the next twenty-five years, I think we can confidently say that they will be an even larger palaeontological phenomenon.

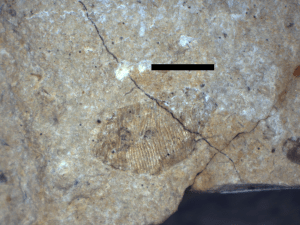

As you might expect from the first thylacocephalans in a new land, they contained at least one new species. The distinct shape and structure of the taco-shell being the key feature here. Most thylacocephalans have a smooth outer shell, but the Strawberry Bank specimens were notable for having distinctive grooving on the carapace surface.

The species was dubbed Thylacocephalus fewlassi, with the species name originating from the word Fewlass, which means rough and uncouth, a perfect description of the shell though not so much for the person after whom the animal was named, Dr Hels Fewlass, an archaeological scientist who is still a good friend to me and provided a great deal of fun and support during that Masters year. Though whether the act of naming a bizarre dangly legged, planktonic arthropod after someone is a compliment or an insult remains up for debate.

If nothing else, it did at least lead to one of my all-time favourite interactions from my years of doing science communication, and I apologise in advance to Hels for sharing this story but it is just too funny not to. When chatting about naming new species, using T. fewlassi as an example for the reasoning behind an animal name, the eight-year old school girl I had been talking to immediately responded to the anecdote by asking, “Was she your bit of rough?” You really never know how a child is going to respond to SciComm do you?

References

Charles, R. (2015) The crustaceans of the UK’s forgotten lagerstätte. University of Bristol Masters Thesis

Jobbins, M., Haug, C., & Klug, C. (2020) First African thylacocephalans from the Famennian of Morocco and their role in late Devonian food webs. Scientific Reports 10, 5129

Edited by Elvira Piqueras Ricote, Kim Chandler, & Fionn Keeley