Guest Author: Dr Rachel Kruft Welton

Current Palaeontology MSc Student

In 2013 we went on holiday to Portugal. It was blisteringly hot every day and sightseeing involved an effort of will. I was, however, not going to miss out on the famous dinosaur tracks that litter the Lusitanian Basin around Lisbon. We parked next to the Nossa Senhora de Cabo on the Espichel Coast and made our way over the cliffs, down a stony path. We were near two sites containing trackways: one called Pedra da Mua and the other called Lagosteiros.

On the rocky floor, a row of semi-circular dents tracked diagonally away under our feet, down the hillside. The pictures do not really do justice to the feeling of standing in the shoes of a dinosaur 130 Ma old. The question, of course, is what sort of dinosaur made these prints? Plenty of work has been done on identification, but there are many tracks belonging to several types of dinosaurs. Can I work out which tracks we were looking at from the family photos I took at the time? Let’s do some detective work.

Trace fossils, such as footprints are called ichnofossils, and there are a dozen sites where ichnofossils can be seen in Portugal, ranging in age from the Lower Jurassic to the Lower Cretaceous. At present, there are five dinosaur track sites in Portugal designated as Natural Monuments, three of them in the Sesimbra area. The Lagosteiros and Pedra da Mua tracks fall within the Arrábida National Park, where we were staying.

You can get a good look at one trackway in this video

In the 15th century, people from the Sesimbra region interpreted the dinosaur footprints on the cliffs of Cabo Espichel as a religious artefact. The story goes that the Virgin Mary was carried vertically up the cliff from a stormy sea to safety on a “giant mule”. The mule disappeared, leaving only its footprints. This tale drew pilgrims from all over, and during the 18th century the Cabo Espichel Sanctuary was constructed to accommodate all the visitors. The footprints from the mule story are actually Upper Jurassic sauropod footprints.

There are several levels with dinosaur trackways between Cabo Espichel and Lagosteiros bay. Pedra da Mua (where the legend of the mule originates) has nine trackways, made by as many as 38 different animals. One set show the progression of three juvenile sauropods, followed by adults, trekking through the Jurassic mud. It is evidence for sauropod herding behaviour. Sauropods tend to leave very widely spaced prints, whereas bipedal dinosaurs will leave narrower gauge prints.

Several tracks show beautifully preserved theropod footprints, with toes clearly preserved. One track even has theropod* foot prints with different stride lengths, right compared with left, showing the animal had a limp. (* Some websites claim the limping animal was a sauropod.)

The Lagosteiros tracks, just half a kilometre from the Pedra da Mua site, date from the Lower Cretaceous, and are the only Cretaceous trackways in Portugal. One track shows a bipedal theropod moving at around 15km/hr, but others were made by some sort of ornithopod, where the footprints are just shallow depressions in the rocks.

But which of the many trackways had I actually seen? From studying a map of the area, I’m pretty sure we were looking at the Lagosteiros site, rather than Pedra da Mua, so the prints were Lower Cretaceous. But was it a sauropod, a fast moving theropod, or an ornithopod that had made those prints?

I think I can rule out the sauropod, as the tracks are narrow gauge, which means I need to work out how fast my dinosaur was moving to see if I had stumbled across the sprinting theropod tracks, or the slower moving ornithopod tracks.

There is a way of working out how fast an animal was walking from its footprints. The calculations generally come out between 1 and 4 m/s (human walking speed), but occasionally a dinosaur shows a turn of speed, and the calculation shows they can be as fast as 15 m/s (around 35 mph), like the theropod, if they are chasing lunch or trying to avoid being lunch.

The calculation comes in an original form, (as described by Alexander 1976) as well as a simplified form. They don’t give quite the same answers, so we will try them both and see if we can get a ball-park figure. For my own amusement, I will try to reconstruct the speed of the dinosaur that made these prints.

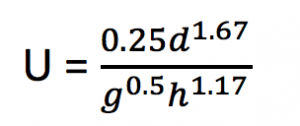

The original equation:

Where u = velocity in m/s

d = stride length

g = gravity (we will use 9.8 m/s2)

h = hip height, where hip height is 4 to 6 times the footprint length

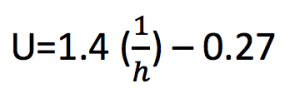

The simplified version is

Clearly there is no scale in the first photo, but fortunately I took a photo with each of my children sitting in a footprint, so we can make a guestimate for each of the values.

The stride length is the distance one foot moves, so it is the distance between alternate children. If the dinosaur is walking towards us, then the right foot stride length is from my daughter in the purple top to my son in the straw hat, and the left foot is between my other two daughters. Either way, this is over 2m. I estimate 2.2 to 2.6m. Feel free to pick different numbers.

The hip height can be calculated because it is between 4 to 6 times the length of the footprint. Each print is the exact size of a child’s bottom, so around 30-40 cm (Santos et al (2008) suggest 38-46 cm, but I can’t know for sure which footprints they measured). The smallest hip height would therefore be 4 times 0.3 = 1.2m, and the largest 6 x 0.4 = 2.4m

Plugging those numbers into the formulae, using upper and lower bounds, gives us a range of possible values.

Original formula gives us between 0.11 and 0.32 m/s, which is between 0.24 and 0.72 mph.

Simplified formula gives us between 0.31 and 0.90 m/s, which is between 0.71 and 2.02 mph.

The speed common to both methods is 0.72 mph, just under three-quarters of a mile in an hour. Whichever method we use, this animal was taking its time, plodding across the Lower Cretaceous landscape. I think we can safely conclude that these were not the prints of the racing theropod. It seems that we were sitting in the prints made by a slow-moving ornithopod.

References

Alexander RM (1976) Estimates of speeds of dinosaurs. Nature 261:129-30

Santos VF, Silva, DM & Rodrigues LA (2008) Dinosaur track sites from Portugal: Scientific and cultural significance. Oryctos vol 8: 77-88

Tourism websites such as:

used to try to locate which footprints we visited. Accessed 2nd September 2020.

Edited by Rhys Charles & Fionn Keeley