One thing we palaeontology communicators repeatedly tell people is that not all dinosaurs were the giants most picture when they hear the name. Many dinosaurs were small, taking up the niches of the nippy little insectivores and seed eaters we see in their modern bird counterparts. However, there’s no denying that when it comes down to it, everyone loves a big dinosaur for the simple reason that they were big. No need to look for any deeper meaning. Big animals are cool.

That’s why when the news broke earlier this year of the largest dinosaur ever discovered in Australia, the palaeo world was instantly enamoured.

Remains of the giant were first uncovered near the town of Eromanga in Queensland. For reference that’s about 900km west of Brisbane, and yes, I realise what a crazy distance that is for a reference point – welcome to Australia.

Quickly identified as a long-necked sauropod, the creature was dubbed Australotitan cooperensis (after the southern location, size, and nearby Cooper Creek formation) [1]. As might be expected from such a big dinosaur, the fossils took a long while to fully excavate, with the first bones being retrieved in 2005 and some not being recovered until five years later. In the decade since then the specimen has spent much of its time hiding away from public knowledge before being properly studied.

A number of fossils were found of this dinosaur, but when it comes to estimating the sizes of extinct vertebrates, some bones are more useful than others. Namely, what scientists really wish to find for a fairly accurate estimate is a femur, and oh boy does this dinosaur have a femur (well it has two – but only the right one is complete). The sauropod femur measures over 2 meters in length (2146mm to be very precise). This thighbone would indicate a total length for the animal of nearly 30m, making it not only the largest animal ever discovered in Australia, but one of the largest terrestrial animals full stop.

Of course, this initial measurement may well be revised with further study, potentially to a smaller figure. This is often the case when it comes to descriptions of these gigantic sauropods, for the simple and rather infuriating reason of scientific ego.

When you don’t have a full skeleton and are estimating body mass and size from fragments, you get a range of possible results and, in order to grab the spotlight, it is annoyingly common for scientist to proclaim the uppermost estimates as the definitive measurement. One decent-sized femur and suddenly a researcher is claiming their dinosaur would have spanned multiple time zones, because it’ll make a good attention-getting headline in this palaeontological pissing contest.

The measurements may sometimes be a bit flawed, however, they are still certainly good enough to be able to put forward a list of contenders for a question this recent paper got me pondering. What is largest dinosaur you can find on each continent?

This is actually a harder question to answer than you might think, partly due to the aforementioned egos and exaggerated measurements, but also because this is one of those questions Google seems incapable of answering. If you go to that search engine and type your query, say “What is the largest dinosaur in Africa?” it will give you a wildly incorrect result.

In that example, the result it churns out in huge bold letters is Ledumahadi. Now that is indeed a dinosaur, so I suppose that’s half the battle. But at only 9 meters in length, it’s far from the biggest the African continent had ever seen. Not to say that Ledumahadi isn’t an interesting animal of course. In fact the reason Google gets so confused is because it was one of the very first large dinosaurs, though, living in the early Jurassic, the dinosaurs had well over a hundred million years of potential growing time left in them.

So if this question can’t be answered by Google, I suppose it’s up to me to do the leg work. Let’s do a bit of digging…

Europe

Seeing as we’ve already covered the other side of planet with Australia, let’s next think of our own backyard; what was the largest dinosaur you could find in Europe?

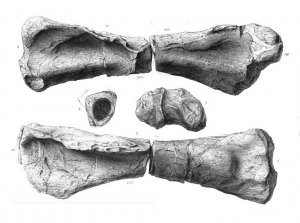

Amongst the potential winners of this title is Duriatitan, the largest known dinosaur from the United Kingdom [3]. This species is known only from a single fossil, but thankfully that fossil is quite indicative. A huge humerus from the Jurassic Kimmeridge Clay near Weymouth shows that this sauropod dinosaur may have had an estimated length of 25m (that’s a little bit longer than a full-sized tennis court).

To further compound my earlier point about specimens hiding in museum storerooms, incredibly, despite its clear importance and natural intrigue, Duriatitan was not formally named by science until 2010, even though the fossil was discovered in 1874. The poor forgotten giant was misnamed and unknown for 136 years. And then had to wait another 11 years before it finally caught a big break, featuring in a renowned, popular, and internationally respected blog such as this.

However, this is just the UK, not all of Europe. If you look to the mainland you find that Duriatitan isn’t far off that record though; along with a few others of similar size, such as the Dinheirosaurus of the late Jurassic of Portugal. But maxing out the scale of Europe is Turiasaurus, a giant titanosaur that may have reached nearly 30m in length [4].

Turiasaurus was first discovered in Spain, specifically in Riodeva, about 30 miles North-West of Valencia. First described from a partial left forelimb, other fossils have revealed a few surprising things about the animal. In particular, the skull of Turiasaurus was smaller than you may expect at only around 70cm in length. A smaller head being one of the necessary adaptations to having such a long neck – any larger and you’re going to encounter some pretty basic balancing issues.

To have a larger head would require stronger neck musculature, meaning vast amounts more muscle mass, and, as counter-intuitive as it may sound, weight-saving is very important when an animal grows as big as these sauropods. They may be huge but their bodies are littered with evidence of weight-reducing measures, most notably air sacs within their bodies and bones. You can see evidence of these in the structure of their vertebrae. Their living relatives, the birds, also have these biological body bubbles within them. They use these to save weight for flight; though this is something you are highly unlikely to ever see a sauropod attempting.

Africa

The huge continent of Africa is no stranger to giant animals, being home to the current largest terrestrial species on the planet, the African Elephant. And looking into the Mesozoic you find similar giants, including some of the largest theropod species known to science, like Carcharadontosaurus and the famous sail-back Spinosaurus.

But as any seven-year-old will tell you, the theropods are never a contender for largest dinosaur when there are sauropods about, and Africa has plenty of those too.

One of the most famous African sauropods is Jobaria, a Jurassic beasty found in the heart of the vast Sahara desert. This animal may not have been the largest of the bunch (measuring 18m in length) but thanks to a remarkable discovery in Niger it is one we know a lot about. In the late 1990s, a skeleton was recovered 95% complete [5].

When you’re dealing with fossils of creatures millions of years old, it’s far more common to find mere fragments (as evidenced by animals like Duriatitan earlier). So to find one basically intact like this is hugely significant, and over twenty years later this specimen actually still holds the record for the most complete sauropod dinosaur ever found, thanks to the flash flood event which buried it (and a host of other dinosaurs in this area). So many bones are to be found here in fact that they inspired local legends with the Tuareg nomads (Jobaria being named after a mythical creature called the ‘Jobar’).

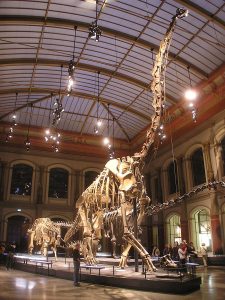

The winner of the largest known sauropod/dinosaur in Africa is also the owner of what is, in my opinion, the best name (or at least the most fitting) in the list of continental giants, Giraffatitan, literally translating into the ‘Titanic Giraffe’.

If you want a sense of scale for this animal, imagine a fully-grown modern-day giraffe. And now, imagine that this giraffe has another giraffe balanced precariously on top of its head. That second giraffe would be able to make eye contact with Giraffatitan, or it rather it would just be able to for half a second before plummeting back down to earth. For those who insist on actual units of measurements besides ‘Stacked Giraffes’, that’s 12m off the ground.

And in case you still can’t get your head around that figure, all you need do is book a flight to Berlin and pop into the Dinosaur Hall of the Museum für Naturkunde, where you can use yourself as a scale bar by standing next to the enormous mounted skeleton that forms the centrepiece of the hall.

Well, look at that. When I started writing this article I felt confident that I’d be able to fit it in one entry, but with the word count already getting well above 1500 and still having four continents to go I think it might be best to split this one up. So we’ve covered Australia, Europe and Africa, still got the Americas, Asia, and Antarctica still to go! Keep an eye out for a future post coming soon!

References

[1] – Hocknull, S.A. et al. (2021) A new giant sauropod, Australotitan cooperensis gen. et sp. nov., from the mid-Cretaceous of Australia. PeerJ 9:e11317 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.11317

[2] – McPhee, B.W. et al. (2018) A giant dinosaur from the earliest Jurassic of South Africa and the transition to quadrupedality in early sauropodomorphs. Current Biology 28, 3143 – 3151

[3] – Barrett, P.M., Benson, R.B.J., & Upchurch, P. (2010) Dinosaurs of Dorset: Part II, the sauropod dinosaurs (Saurischia, Sauropoda) with additional comments on the theropods. Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society 131, 113–126

[4] – Royo-Torres, R., Cobos, A., & Alcalá, L. (2006) A giant European dinosaur and a new sauropod clade. Science 314, 1925-1927

[5] – Sereno, P. C. et al. (1999) Cretaceous Sauropods from the Sahara and the uneven rate of skeletal evolution among dinosaurs. Science 286, 1342 – 1347

Edited by Mike Hynes

Rhys Charles graduated from the University of Bristol with an MSci degree in Palaeontology & Evolution in 2015. He is now the Engagement Officer for the Earth Sciences department and Public Engagement Associate for the Faculty of Science, as well as being a freelance scientific author.