Halloween Special 2023

The Zombie Apocalypse is a common Halloween trope. It’s a time when the idea of the dead rising from the grave is not only accepted, but actively celebrated. And to the surprise of none, amongst the rotten hoard this year is a familiar face; the BDP Blog.

We’ve done Halloween special posts before, like when we explored the spookiest thing about bats. This year though we’ll be matching icons of horror media with their prehistoric equivalents in a listicle. That’s right, the true horror here is that we’re going full Buzzfeed.

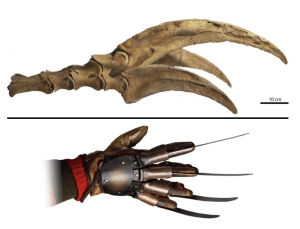

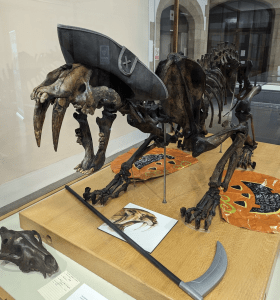

Freddy Kreuger

There is perhaps no more obvious analogy between Palaeontology and Horror film villains than that of the blade handed bloke from Elm Street and the bizarre scythe-armed theropods, the Therizinosaurs. I’ve put this one first because, let’s be honest, a lot of you only clicked on this article to confirm that I included it.

The blades Krueger possessed were a few inches long, steel, and attached to a glove he wore on his right hand. Therizinosaurus meanwhile had claws a meter long, on both hands, and far from a glove, they had cores of bone coated in a keratin sheath, fused to their hands by fleshy tissue. I may have glammed up the description there to make it sound cooler, but it is. Let’s be honest, Krueger wears a prickly mitten, Therizinosaurus is the real deal.

Where they differ is how they used them. Krueger goes into the dreams of teens and murders them in their sleep, as revenge for being burned in a boiler room by their parents. Typical family movie hijinks. Therizinosaurus’ motives however were a bit more pure.

Despite being part of the theropoda (the group including the vicious hunters like Tyrannosaurus), Therizinosaurus was a herbivore. Its head was reduced in size and perched atop a slender neck. Those claws, were probably used to rake down foliage from the trees. Less Grim Reaper, and more regular reaper. Less Nightmare on Elm Street, and more Nightmare for Elm Trees. I’ll stop with the wordplay now.

That is if they had any real function at all of course. Biomechanical analysis of the claws has shown no real mechanical functional speciality, leaving them a bit mysterious. They apparently weren’t actually that good for anything.

We also have no information on the plumage colour of Therizinosaurus. Thus we can’t rule out that this dinosaur was patterned with green and red horizontal stripes like Freddy’s sweatshirt. There would be absolutely no evolutionary benefit to this colouration whatsoever, but I’m saying there’s a chance.

So that’s one of our Halloween connections down, and by far the clearest cut. Brace yourselves, the rest are a lot more tenuous.

Leatherface

No piece of machinery screams horror film than the humble chainsaw. This obnoxiously loud wood reducer was most famously wielded by dedicated family provider, Leatherface, in 1974s Texas Chainsaw Massacre. But could evolution ever create something as elegantly beautiful as a chainsaw?

In short, not so much. Circular rotation of this kind isn’t really found in nature (or at least on a visible scale – the tiny processes by which cellular flagella move actually do function somewhat like this, so they are in actuality everywhere, but this isn’t a blog on cellular biology).

Spirals are far more common, like in the iconic ammonites. Some of these ammonites have their keels ornamented with spines, and I suppose you could liken them to a prehistoric chainsaw, but there is a better contender out there.

The teeth of sharks are common fossils the world over, due to their high preservation potential, and due to sharks being so widespread and having constant tooth replacement (rotary dentition – which you could claim is a very slow acting version of nature’s chainsaw).

Though the teeth of their relative Helicoprion stand out above the others. Fossils of their teeth are found in a mathematically-pleasing spiral whorl, unlike any other organisation seen in their modern relatives (which, for the record, are actually Ratfish and not true sharks).

Admittedly the way the whorl would sit in the mouth made the animal resemble a buzzsaw more than a chainsaw, but it would be close. And some of these teeth could reach 14cm, giving an estimate for the full animal of over 7.5m, significantly larger than the tool used by Leatherface (anything above 1.5m is just excessive).

It’s thought that Helicoprion would have fed largely on soft bodied cephalopods, and the descriptions of how the ‘buzzsaw’ functioned make for horrific reading on their own; ripping ammonoids out of their shells, then slicing through their flesh and mashing them up between their jaws. It could fittingly go with the horror theme of “Drag Me To Hell” too, but with less bank loans.

(Oh, and yes, Helicoprion fossils have been found in Texas).

Hannibal Lecter

For such a supposed connoisseur of the fine arts, Hannibal Lecter certainly does have poor taste in drinks. I’m referring of course to the fact that a chianti doesn’t pair well with dark meats, and as such would be a bitter accompaniment to a meal of liver and fava beans, a combo he suggests in 1991’s Silence of the Lambs. Though it might seem odd to be taking issue with his wine pairing choices over his penchant for eating people, cannibalism does at least appear a few times in the natural world, making it the far less heinous crime.

Though it’s been suggested for a few dinosaur species, some of the strongest evidence for a carnivore sourcing their meat so extremely locally is Majungasaurus. This abelisaurid (small-armed, strong-legged, and stout-faced theropods – think the Carnotaurus from Disney’s Dinosaur) lived on Madagascar, already an island by the late Cretaceous.

Tooth marks on the bones of Majungasaurus specimens appear to match exactly those made by their kin. The fact that these traces all seemed to happen post-mortem means that we can’t be sure that it was Manjungasaurus itself who had been the killer as well as the diner, but we can’t rule it out either. It’s possible that competition for resources on the island meant that having an old friend over for dinner was the only course.

And if ever apprehended for their crimes, the mask would still be necessary, but Barney could forgo with the straight jacket. Abelisaurids had notoriously tiny arms, and there’s no way Majungasaurus could reach up and undo the straps.

Dracula

Let’s not overthink this one when Vampire Bats literally exist. Now whether there is evidence of blood sucking vertebrates in the fossil record is trickier, as it’s a difficult behaviour to prove and quite a narrow ecological niche.

Fossil evidence of Vampire Bats goes back to the Pliocene of Venezuela, and some of the earlier species may have been 25% larger than those found today. Admittedly that’s not exactly a mind-blowing figure of a past giant, but bats aren’t exactly pterosaurs when it comes to maximising scale.

Though it may be a cool thing to end this section of the article by saying there are definitely dinosaurs who survive by drinking the blood of others. But in a similar hype-killing move I can confirm I’m of course speaking of modern small birds like Oxpeckers, and not giant scaled theropods.

Jigsaw

As far as science can tell, no creature has ever utilised mechanical traps (which are for some reason regularly kind of dripping wet with no explaination?) to act out needlessly gory games on victims. But absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

Traps do exist in the natural world, and animals will frequently fall prey to them. The tar pits of La Brea in California have preserved thousands of animals from the last 40,000 years, including Giant Ground Sloths, and Sabre-toothed cats. We actually have one of these Smilodon specimens in the foyer of our Earth Sciences Department in Bristol.

It’s believed that many of the animals found here may have first been tempted to the area for a drink, standing rain water sitting atop the tar and concealing its true nature. Their thirsts quenched they realise they can’t move their limbs, now lodged in the goo. They are left with a choice, sit there and die, or cut off their own limbs and maybe escape, perhaps with a new sense of respect for their lives (most Pleistocene macrofauna are so ungrateful to be alive, but not them, not anymore). See? It’s literally Saw.

Human remains have also been found in the La Brea Tar Pits, so we can’t entirely rule out the idea that there weren’t people morbidly watching animals trapped in the mud over 10,000 years ago. And who’s to say that, in whatever way they communicated back then, they didn’t utter their equivalent of “I want to play a game.”?

(Bear remains have come from La Brea too, meaning you can forget Saw’s ‘Reverse Bear Trap’, because this is a literal Bear Trap).

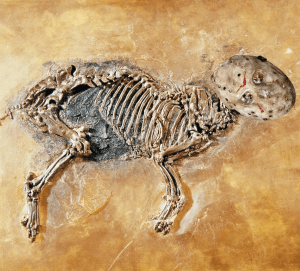

Jason Vorhees

Before anything else, a nit-pick. Jason wasn’t even the main villain of the first Friday the 13th movie (sorry if that’s a spoiler but the movie is over 40 years old and I’ve not said who the actual killer is, so you can still go watch it). But he did drown in a lake, meaning in a way, Jason is represented by all fossils who were preserved in lacustrine sediments. Such a setting has been responsible for some amazing fossil locations, such as the Messel Sediments of Germany, and Jehol Biota of China.

Had Jason not gone on to put on a hockey mask and seek revenge on promiscuous teens, I’m sure he would have made a fine fossil from the future lagerstätte of Crystal Lake. But no, he chose to go to space instead.

Conclusion

As could be predicted, by the end of this article the comparisons became abstract to the point of matching characters with the concepts of depositional environments. As such it’s probably best to cut the article there, but hopefully it’s been an entertaining and informative jaunt through the intersections of palaeontology and horror films, with enough niche references to keep the cinephiles as happy as the palaeos. Happy Halloween all!

About The Author

Rhys Charles is the Engagement Officer for the Earth Sciences department of the University of Bristol, and has headed the Bristol Dinosaur Project since 2016. (@tweetodontosaur)

References

Czaplewski, N. J. & Rincón, A. D. (2020) A giant vampire bat (Phyllostomidae, Desmodontinae) from the Pliocene-Pleistocene El Breal de Orocual asphaltic deposits (tar pits), Venezuela. Historical Biology. 33, 2438 – 2443

Lebedev, O.A. (2009) A new specimen of Helicoprion (Karpinsky, 1899) from Kazakhstanian, Cisurals and a new reconstruction of its tooth whorl position and function. Acta Zoologica. 90, 171-182

Pardiñas, U.F.J. & Tonni, E.P. (2000) A giant vampire (Mammalia, Chiroptera) in the Late Holocene from the Argentinean pampas: paleoenvironmental significance. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 160, 213-221

Qin, Z., Liao, C., Benton, M.J., & Rayfield, E.J. (2023) Functional space analyses reveal the function and evolution of the most bizarre theropod manual unguals. Communications Biology. 6, 181

Rogers, R.R. et al. (2004) Paleoenvironment and paleoecology of Majungasaurus crenatissimus (Theropoda: Abelisauridae) from the late Cretaceous of Madagascar. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27, 21-31