Guest Author: James Ormiston

Palaeontology MSci Graduate / Palaeoartist

You very likely know the rhyme “She sells sea shells on the sea shore”. You may also have heard that it was inspired by the famous Dorset fossil hunter Mary Anning. You may, or may not, know that it’s potentially unlikely that Anning was the real inspiration for the rhyme (the rhyme is much older than many people realise). It makes for a nice story though!

But how about this alternative… “She finds fish fins from the far firth”? It’s not a true folklore tongue twister – because I just made it up – but the woman it describes is very much real. Like Anning she represented a rare breed: the Victorian “Lady Geologist”. Women were, in general, not uncommon in 19th Century geology. The wives of men like William Buckland were also trusty research assistants, but it was unusual to find a woman dictating her own way in the perceived gentlemanly field of earth science.

Women were thought to lack the rationality and resilience to handle scientific debate and fieldwork. The male attitude was that delicate flowers are easily crushed by heavy rocks and heavier ideas. This was a division that even social class did not counteract, as was the case with Lady Eliza Maria Gordon-Cumming. Her long name may give a clue that her background was markedly different to Mary Anning’s.

While Mary was born into modest surroundings, the daughter of a cabinet maker, Lady Eliza was the daughter of a politician and a celebrated novelist. Mary lived in a small wave-battered house on a bridge in Lyme Regis, while Lady Eliza occupied the enormous, centuries-old Altyre Estate in Morayshire, Scotland. Mary’s adventure into prehistory was initially driven by financial necessity to supplement her family’s poor income from an early age. Lady Eliza picked it up almost as a hobby in her 40s after having 12 children, and often had other people dig fossils up for her.

Part of the reason behind Lady Eliza’s relative obscurity is the tragic brevity of her activities. Despite amassing potentially hundreds of fossils, many of which are now housed in museums in Scotland, England and Switzerland, she died in 1842 only 3 years after her introduction.

Lady Eliza was already a woman of science, as she was an accomplished horticulturalist respected for her flower crosses. But the discovery of exceptionally well-preserved fossil fish at a nearby limestone quarry steered her towards more ancient life forms. Her interest in fossils was further influenced by the arrival of some famous geologists of the time who were investigating Scotland’s Old Red Sandstone formations. Lady Eliza would join them on their trips around the Moray Firth, as reminisced by her travel-writer daughter Constance…

“Among my vivid memories of about 1840 were certain evenings when my mother returned from distant expeditions escorted by several gentlemen, whom I now know to have been Sir Roderick Murchison, Hugh Miller, Agassiz, and other eminent geologists, who at that time were deeply interested in the newly discovered fossil fish in the Old Red Sandstone in Ross-shire, on the other side of the Moray Firth. Similar fossils had just been found in the Lethen-bar Lime Quarries, on the other side of the Findhorn. These were a source of keen interest to my mother, and it was to search for more that the geologists were invited to Altyre.”

Lady Eliza was able to use her personal wealth and connections to great effect. She paid workers to bring her fossils found at the Lethen Bar quarry (which no longer exists, but its location has been deduced from historical records by Andrews, 1983), paying more for high quality specimens. She would then apply her keen artistic talents to create detailed drawings and paintings of some of the best finds with the help of another daughter, Anne. Past visits by the artist Sir Edwin Landseer (Britain’s most financially successful Victorian artist, creator of the Trafalgar Square lions) had initially inspired her to take up painting, and illustrations of the fossils in her collection drew the attention of many notable researchers. Constance again recollects…

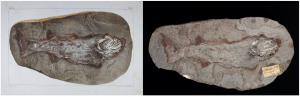

“Evening after evening there was great excitement in carefully lifting from a dogcart the spoils of the day, namely grey nodules which, when gently tapped with a hammer, split in two, revealing the two perfect sides of strange fossil fishes, with the very colour of the scales still vivid. Day by day my elder sisters patiently made minutely accurate water-colour studies of these, and the best specimens were sent to the British Museum, where they still remain, and where certain fishes hitherto unknown, were called after my mother.”

Among her newfound academic acquaintances was Louis Agassiz of Switzerland, an expert in the field of palaeoichthyology who was delighted to find that most of her collection comprised Devonian fossil fish (he is also a controversial figure due to his troubling views on race, something that reached into the highest echelons of science at the time, such as the “Father of Palaeontology” Georges Cuvier, of whom Agassiz was a student). He trawled through the mountain of piscine remains and identified a number of new species. In the publication of his influential work on Devonian fish, “Monographie des poissons fossiles du vieux grés rouge: ou système Dévonien (Old Red Sandstone) des Iles Britanniques et de Russie”, he consistently thanks Lady Eliza for her generous contributions (translated from French)…

“Among the recent contributions that have most increased our knowledge on the fossil fish of the Devonian system, I must put in the first line what Lady Gordon Cumming did in order to illustrate this ancient fauna. Not content with collecting and distributing to geologists, with unequalled liberality, the numerous copies of these precious debris which she had collected in a quarry exploited for this purpose, she studied them carefully, set apart the most perfect copies, and painted them with a precision of detail and an artistic talent that very few naturalists were able to achieve. So her drawings and those of her daughter, who constantly assisted her in these studies, will form one of the main ornaments of my Monograph. By delivering this collection to the public, it is painful for me to think that this noble Lady will no longer be able to collect the tribute herself so justly deserving of the recognition of geologists. May this memory, sown on her grave, remind her worthy follower that the eagerness she put in assisting her mother contributed to raising a lasting monument in the scientific world!”

So enamoured was Agassiz with the Altyre Collection and its accompanying illustrations that he named one of his newly found species after Lady Eliza; Cheirolepis cummingae. Agassiz had similarly named new species after Mary Anning and Elizabeth Philpot. But perhaps it was down to fate that, along with much of her potential legacy, this particular species was also lost to history when it was invalidated and merged with C. trialli in 2015.

There were many other collectors and illustrators working on the fossils of Scotland at the time, so Lady Eliza and her daughter were not alone in their efforts. But it may well have been a combination of the sheer volume of specimens, their diligent visual recording and the boost of the family’s social class that led to Agassiz, Murchison and others ensuring that the Altyre Collection received the praise that it did. This was a time of great excitement in the palaeontological community as the Old Red Sandstone was being intensely surveyed, and many of Lady Eliza’s fossils were very important in this “Devonian Enlightenment”.

But still, despite her entrepreneurial enthusiasm and friendship with the highest authorities of the day, Lady Eliza was still Lady Eliza. The glass ceiling for women in the scientific workplace was severely stunting. That she was credited at all is quite a significant occurrence, considering that even the now-world famous Mary Anning was seldom credited for her finds. Women were, as mentioned, welcomed as assistants contributing observations, data, illustrations and the like. But they were not expected to come up with their own ideas and interpretations. It wasn’t seen as “proper” to be able to think for themselves.

This is implied by the outcome of Lady Eliza’s transition from specimen illustrations to scientific reconstructions. There were many species in her collection only known from partial remains, and so by way of simple concepts of symmetry she started having a go at reconstructing what was missing. She was, in her final days before succumbing to birth complications, intent on presenting her ideas to the scientific community by reconstructing the fishes Pterichthys and Cocosteus. She sent out her interpretations to Murchison, hoping to have them published alongside his famous work on the Silurian. But shortly after her death, her daughter Anne also wrote to Murchison, this time apologising for Lady Eliza’s “fanciful” reconstructions and her combining of multiple fragmentary specimens into a hypothetical complete one. Anne asked that the reconstructions be withdrawn.

Burek & Higgs (2007) reason that this act of backtracking demonstrates the double standards of the time. Both William Buckland and Richard Owen had themselves been very much “fanciful” in their incorrect reconstruction of the dinosaur Iguanodon having a nose spike, which should have been on its thumb. Even Hugh Miller, another of Lady Eliza’s contacts, had merged specimens of fish from the Old Red Sandstone itself. Why did Anne see it necessary to formally apologise for something other scientists had been guilty of but not been persecuted for? The fact that Murchison’s personal journals were riddled with sexist remarks about women in science is unlikely to be a coincidence…

What else may she have accomplished were she not lost so soon after embarking on her prehistoric journey? We will sadly never know. From the year of her passing there is a trail of breadcrumbs in various publications, including the Proceedings of The Geological Society of London and The Literary Gazette, briefly reminding the world of her existence and thanking her in a couple of lines and footnotes. Had she continued her work, and maintained the inquisitive determination to bring her finds to life (aided by her high societal standing), Lady Eliza could well have become one of the first professional female palaeontologists. As put by the ancient Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu: “The flame that burns twice as bright burns half as long.”

References:

Aggasiz, L., “Monographie des poissons fossiles du vieux grés rouge: ou système Dévonien (Old Red Sandstone) des Iles Britanniques et de Russie” (1844-45)

Andrews, S. M. “Altyre & Lethen Bar, two Middle Old Red Sandstone fish localities?” (1983)

Burek, C.V. & Higgs, B., “The Role of Women in the History and Development of Geology” (2007)

Gordon-Cumming, C. F., “Memories” (1904)

“Proceedings of The Geological Society of London. November 1838 to June 1842. Vol. III” (1842)

“The Literary Gazette and Journal of Belles Letters, Arts, Sciences, &c. For the year 1842.” (1842)

Winick, S., “She Sells Sea Shells and Mary Anning: Metafolklore with a Twist” (2017)

Edited by Rhys Charles