Guest Author: Jack Lovegrove

Current Palaeontology & Evolution MSci Student

Red pandas are undeniably cute. This has made them a rising star of pop culture; they have even starred in their own Netflix cartoon the adorable ‘Aggretsuko’. They seem to be increasingly stealing some of the spotlight from their giant namesake. Beyond just being cute however red pandas have a fascinating evolutionary history. These quirky bamboo eaters are the last survivors of an evolutionary dynasty whose domain once stretched from Spain to Tennessee. Consider this article both a dive into the niche subject of fossil red pandas and as an excuse to look at cute red panda photos online.

Before we can venture any deeper into the red panda dynasty, we need to look at some taxonomy (I’ve balanced this section out with a cute red panda picture). The scientific name for the red panda is the grandiose Ailurus fulgdens which roughly translates to “Shining Cat”, but we know now that red pandas sit on the dog rather than the cat side of the mammalian carnivore family tree. More specifically they are the lone extant example of the family ailuridae, the sister group to the raccoon family (procyonids). By way of contrast the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) is a specialised member of the bear family, Ursidae.

Red pandas are the only surviving members of the family Ailuridae, but should we consider all its extinct members red pandas? There is not necessarily a right or a wrong answer to that question. To make the case for my stance I am going to highlight one of the best known primitive ailurids Simocyon batalleri. This species was big, weighing around 60kg or roughly the size of a puma and its teeth still showed specialisations for eating meat. It does have the “false thumb” of a modern red panda (really a modified part of the wrist known as the radial sesamoid), but Simocyon probably used it for climbing trees rather than grasping bamboo. A puma-sized predator that might be stalking you from the treetops is not exactly what people think of when they hear the words red panda. For this reason, I am going to only use the name red pandas for members of the sub-family Ailurinae.

The earliest known member of Ailurinae shows up in the middle Miocene of Spain (16-17mya) alongside Simocyon. Its lengthy name of Magerictis imperialensis belies its scrappy remains consisting of a single isolated molar. This tooth is starting to show well differentiated cusps, the raised areas that run around the edge of a molar. In living red pandas these well differentiated cusps are used to grind up the tough plant material that dominates their diet so their appearance in Magerictis suggests it was the first of the red pandas that regularly ate its five a day

At some point in the late Miocene Magerictis or its close descendant spread across the northern hemisphere. During the Miocene broadleaf deciduous forests stretched across Europe, Asia, and North America, with early red pandas scampering through all of them. During the late Miocene and early Pliocene these forests started to break up stranding populations of red pandas in islands of forests across the world. These populations adapted to the local conditions in their small forest chunk forming an impressive radiation of red panda species.

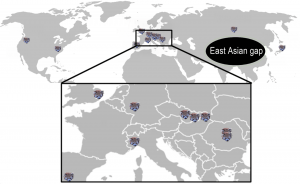

Two species of red panda have been described from the genus Parailurus, the type species P.anglicus (including its synonym P.hungaricus) from the British Isles and Eastern Europe (Slovakia, Hungary, and Romania) and P.baikalus from the Transbaikal region of Asia. However, isolated teeth from this genus have been found across Europe, Japan, and the West Coast of America, suggesting there are a lot of undiscovered Parailurus species out there. Indeed, a complete skull of a new species has been found in Slovakia, a country that for unknown reasons is the red panda fossil capital of the world. Palaeontologists may have their work cut out for them describing new Parailurus species.

Let’s focus for a second on our local Parailurus species P.anglicus. Fossils of this species have been found in the Pliocene of Suffolk. At the time, Suffolk was under a shallow tropical sea with a forested landmass to the west. It’s not known how far west this forest stretched but it’s plausible red pandas were scampering through the treetops of prehistoric Bristol three million years ago. P.anglicus was roughly twice the size of a modern red panda. Although its diet is uncertain it’s not thought to have been a bamboo specialist like the modern red panda. P.anglicus is only known from fossilised fragments of its jaw so many aspects of its palaeobiology remain mysterious.

In 2006 researchers at the early Pliocene Gray fossil site in the Applachians discovered the most complete red panda fossil known to science. It was assigned to Pristinailurus bristoli (sadly not named after the city of Bristol) a red panda that had already been named from that locality. Pristinailurus was bigger than the present-day red panda but its fake thumb was relatively smaller suggesting it spent less time climbing and/or manipulating food than the living red panda. Its molars were specialised for grinding vegetation, but its other teeth were still adapted for slicing meat suggesting Pristinailurus occupied an omnivore ecological niche similar to a raccoon than an extant Red panda. The Gray fossil site ecosystem is worthy of its own article, preserving a fascinating mix of the familiar and the bizarre. It was an oak-hickory forest like those still growing on the slopes of the Appalachians but inhabited by a bizarre cast of extinct animals including dwarf tapirs, giant camels, and hornless rhinos.

At some point an East Asian lineage of these early red pandas became specialised for crunching bamboo. Unfortunately, there is a huge East Asian gap in the fossil record of red pandas, so we are missing the early history of this lineage. This brings us to the extant red panda, or should that be red pandas… a recent study (Hu et al 2020) combined detailed morphological study with modern genetics to show that extant red pandas should actually be split into two subspecies, the Himalayan and the Chinese red panda. Demographic history reconstructions show that these subspecies have had vastly differing fortunes. The Chinese subspecies experienced a population boom during the last interglacial period as it spread throughout the relatively warm Hengduan mountains with a peak population around 50 thousand years ago. By contrast the Himalayan subspecies habitat was constantly threatened by the wax and wane of the Tibetan plateau glaciers during this period causing it to undergo several genetic bottlenecks and population crashes. Both species then suffered major population crashes caused by the last glacial maximum.

I hope I’ve convinced you that even the cutest animals have a rich evolutionary history. Sadly, If the red panda is a relic of a global evolutionary radiation then its present-day population is a relic of a relic. Human activities like logging, farming, and poaching have pushed the red panda to endangered status but anthropogenic climate change may be its biggest threat. Red pandas can only thrive in a narrow temperature band and a warming climate will force them to move further up mountain slopes, moving out of protected areas in the process. At some point they may simply run out of forest to climb up into.

References

HU, Y.; THAPA, A.; FAN, H.; MA, T. et al. Genomic evidence for two phylogenetic species and long-term population bottlenecks in red pandas. Science Advances, 6, n. 9, p. eaax5751, 2020.

KUNDRÁT, M. Chapter 5 – Phenotypic and Geographic Diversity of the Lesser Panda Parailurus. In: GLATSTON, A. R. (Ed.). Red Panda. Oxford: William Andrew Publishing, 2011. p. 61-87.

SALESA, M. J.; PEIGNÉ, S.; ANTÓN, M.; MORALES, J. Chapter 3 – Evolution of the Family Ailuridae: Origins and Old-World Fossil Record. In: GLATSTON, A. R. (Ed.). Red Panda. Oxford: William Andrew Publishing, 2011. p. 27-41.

WALLACE, S. C. Chapter 4 – Advanced Members of the Ailuridae (Lesser or Red Pandas – Subfamily Ailurinae). In: GLATSTON, A. R. (Ed.). Red Panda. Oxford: William Andrew Publishing, 2011. p. 43-60.

Edited by Rhys Charles

All photographs taken by author