Guest Author: Dr Rachel Kruft Welton

Current Palaeobiology MSc Student

Australia has a wide variety of dangerous and venomous creatures. Half the wildlife, it seems, is out to get you. You would have thought, that with the spiders, scorpions, snakes, sharks, blue-ringed octopuses, hungry crocodiles and biting flies, it would be unnecessary to invent a mythological creature intent on devouring humans. However, Indigenous Australians have long described a deadly water-spirit called a ‘Bunyip’. This nocturnal creature resembles a large seal-like dog, about 2 metres long with a dark shaggy coat. It inhabits river margins and swampy areas, where it lays eggs in platypus nests. In some stories it likes to munch on crayfish, and in others, it prefers human children.

Sightings of the bunyip owe much to the imagination of the person reporting the incident, but bones are harder to dismiss, and finds of large bones were occasionally attributed to the bunyip. One such find was in a cave near Wellington, New South Wales, in the early 1830s (Fig 1). The bone deposits were discovered by a local called George Ranken, who drew them to the attention of Major Thomas Mitchell (Dawson, 1985). Mitchell’s collections ended up in London, and in 1938 they were identified by Sir Richard Owen and named Diprotodon optatum.

Diprotodon is named for its two protruding front teeth, which sprouted from a robust skull. To add to the cute goofiness, it had toes that turned inwards (Musser 2019). Its closest living relatives are wombats and koalas, and it is affectionately misnamed the Giant Wombat. It was, however, significantly larger than any marsupial living today, and cuddly, it was not. It was the largest marsupial ever to have lived, topping two metres at the shoulder and nearly four metres in length. It was the size of a hippopotamus, and lived in small familial herds. Comparison of carbon isotopes indicates that herds migrated over 200 km annually (Price et al., 2017), in rhythm with the seasons. They had powerful jaws, capable of eating tough vegetation and preferred dry savannahs to dense forests.

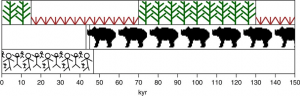

Diprotodon evolved around 2 million years ago in the early Pleistocene, just as the climate was starting to cool significantly. By 150,000 years ago weather patterns were changing and the land was becoming more arid (Kaars et al, 2017). And then, around 45,000 years ago, humans arrived.

The earliest humans coexisted with Diprotodon for the briefest of time. Rock art (Fig 2) showing what could be Diprotodon has been found in a few localities (e.g. Cape York Peninsula), although two of these (Yunta Springs and Wilkindinna) are representations of tracks rather than the animals themselves, and many have now been degraded and exfoliated by the passage of time. Bednarik (2013) remains unconvinced that these depict Diprotodon, as “These taxons are all deemed to have become extinct well before 40 ka ago.”

Humans, it has to be said, do not have a good track record when it comes to shepherding the biodiversity of our planet. The Pleistocene megafauna (creatures over 45 kg) started dropping like flies as soon as humans set foot on each continent.

“The first hints of abnormal rates of megafaunal loss appear earlier, in the Early Pleistocene in Africa around 1 Mya, where there was a pronounced reduction in African proboscidean diversity and the loss of several carnivore lineages, including sabretooth cats, which continued to flourish on other continents. Their extirpation in Africa is likely related to Homo erectus evolution into the carnivore niche space, with increased use of fire and an increased component of meat in human diets, possibly associated with the metabolic demands of expanding brain size. Although remarkable, these early megafauna extinctions were moderate in strength and speed relative to later extinctions experienced on all other continents and islands, probably because of a longer history in Africa and southern Eurasia of gradual hominid coevolution with other animals.” (Malhi et al 2016).

The pattern is the same across Europe, America, Asia and Australia. There was climate change —an ice age was starting —but the arrival of humans, with their efficient hunting practices, cooperative behaviour and use of fire to alter the landscape coincided with megafauna extinctions again and again. Harari, with an eloquent turn of phrase, sums up the evidence:

“…more than 90 percent of Australia’s megafauna disappeared along with the diprotodon (sic). The evidence is circumstantial, but it’s hard to imagine that Sapiens, just by coincidence, arrived in Australia at the precise point that all these animals were dropping dead of the chills.” (Harari 2011)

The story is maybe not so simple for Diprotodon though. Charting the timing of arrivals and extinctions is notoriously difficult. Kaars (2017) determined that the human invasion wiped out the

Australian megafauna within 4000 years, but fossil finds indicate that Diprotodon coexisted with Aboriginal Australians for over 20,000 years (Musser 2019). This suggests that humans may have altered the habitat, and hunted Diprotodon (Fig 3), but that they did not extirpate it alone. The changing climate and increasing aridity of the descending ice-age may have combined to finish off the largest wombat of them all.

So, which is it? Did Diprotodon get wiped out by the human invasion, or did climate change finish them off after a lengthy but uneasy coexistence, or both? It seems that pinpointing the timing of Diprotodon’s extinction is not in itself entirely straightforward. Johnson et al (2016) analysed the fossil record for Diprotodon and concluded:

“There are approximately 100 ages on Diprotodon from more than 1 Myr to 2 ka. After filtering for reliability, only 23 reliable dates remained, none younger than 44 ka.”

This implies that there was no long coexistence with humans. There was no quiet slide into oblivion as the nights got colder and the savannahs drier. Instead, as soon as humans arrived on the scene, Diprotodon, along with the rest of the megafauna, winked out in a geological instant (Fig 4), leaving only some rock art and tales of the bunyip behind.

Although Australian fauna, both real and imagined, appears to be out to get you, humans are not innocent bystanders. No matter how much of a threat the creatures of the wild have been to us, we have been significantly more of a threat to them.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to James Tayler for helpful comments and insight.

References

Bednarik RG (2013) Megafauna depictions in Australian rock art. Rock Art Research 30(2): 197-215.

Dawson L (1985) Marsupial Fossils from Wellington Caves, New South Wales; the Historic and Scientific Significance of the Collections in the Australian Museum, Sydney. Records of the Australian Museum Vol. 37(2): 55-69.

Harari YN (2011) Sapiens: A brief history of humankind. Penguin Random House

Johnson C. N., Alroy J., Beeton N. J., Bird M. I., Brook B. W., Cooper A., Gillespie R., Herrando-Pérez S., Jacobs Z., Miller G. H., Prideaux G. J., Roberts R. G., Rodríguez-Rey M., Saltré F., Turney C. S. M. and Bradshaw C. J. A. (2016) What caused extinction of the Pleistocene megafauna of Sahul? Proc. R. Soc. B.28320152399

Kaars S van der, Miller GH, Turney CSM, Cook EJ, Nürnberg D, Schönfeld J, Kershaw AP and Lehman SJ (2017) Humans rather than climate the primary cause of Pleistocene megafaunal extinction in Australia. Nature Communications 8: 14142

Malhi Y, Christopher E, Doughty CE, Galetti M, Smith FA, Svenning JC, and Terborgh JW (2016) Megafauna and ecosystem function from the Pleistocene to the Anthropocene. PNAS 113 (4) 838-846

Musser A (2019) https://australian.museum/learn/australia-over-time/extinct-animals/diprotodon-optatum/

Price GJ, Ferguson KJ, Webb GE, Feng Y, Higgins P, Nguyen AD, Zhao J, Joannes-Boyau R, and Louys J (2017) Seasonal migration of marsupial megafauna in Pleistocene Sahul (Australia–New Guinea). Proc Biol Sci. 284(1863): 20170785.

Edited by Rhys Charles and James Tayler